In this episode, we tackle the thorny question of AI persuasion with a fresh study: "Scaling Language Model Size Yields Diminishing Returns for Single-Message Political Persuasion." The headline? Bigger AI models plateau in their persuasive power around the 70B parameter mark—think LLaMA 2 70B or Qwen-1.5 72B.

As you can imagine, this had us diving deep into what this means for AI safety concerns and the future of digital influence. Seth came in worried that super-persuasive AIs might be the top existential risk (60% confidence!), while Andrey was far more skeptical (less than 1%).

Before jumping into the study, we explored a fascinating tangent: what even counts as "persuasion"? Is it pure rhetoric, mathematical proof, or does it include trading incentives like an AI offering you money to let it out of the box? This definitional rabbit hole shaped how we thought about everything that followed.

Then we broke down the study itself, which tested models across the size spectrum on political persuasion tasks. So where did our posteriors land on scaling AI persuasion and its role in existential risk? Listen to find out!

🔗Links to the paper for this episode's discussion:

(FULL PAPER) Scaling Language Model Size Yields Diminishing Returns for Single-Message Political Persuasion by Kobe Hackenberg, Ben Tappin, Paul Röttger, Scott Hale, Jonathan Bright, and Helen Margetts

🔗Related papers we discussed:

Durably Reducing Conspiracy Beliefs Through Dialogues with AI by Costello, Pennycook, and David Rand - showed 20% reduction in conspiracy beliefs through AI dialogue that persisted for months

The controversial Reddit "Change My View" study (University of Zurich) - found AI responses earned more "delta" awards but was quickly retracted due to ethical concerns

David Shor's work on political messaging - demonstrates that even experts are terrible at predicting what persuasive messages will work without extensive testing

(00:00) Intro

(00:37) Persuasion, Identity, and Emotional Resistance

(01:39) The Threat of AI Persuasion and How to Study It

(05:29) Registering Our Priors: Scaling Laws, Diminishing Returns, and AI Capability Growth

(15:50) What Counts as Persuasion? Rhetoric, Deception, and Incentives

(17:33) Evaluation & Discussion of the Main Study (Hackenberg et al.)

(24:08) Real-World Persuasion: Limits, Personalization, and Marketing Parallels

(27:03) Related Papers & Research

(34:38) Persuasion at Scale and Equilibrium Effects

(37:57) Justifying Our Posteriors

(39:17) Final Thoughts and Wrap Up

🗞️Subscribe for upcoming episodes, post-podcast notes, and Andrey’s posts:

💻 Follow us on Twitter:

@AndreyFradkin https://x.com/andreyfradkin?lang=en

@SBenzell https://x.com/sbenzell?lang=en

Transcript:

AI Persuasion

Seth: Justified Posteriors podcast, the podcast that updates beliefs about the economics of AI and technology. I'm Seth Benzel, possessing superhuman levels in the ability to be persuaded, coming to you from Chapman University in sunny Southern California.

Andrey: And I'm Andrey Fradkin, preferring to be persuaded by the 200-word abstract rather than the 100-word abstract, coming to you from rainy Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Seth: That's an interesting place to start. Andrey, do you enjoy being persuaded? Do you like the feeling of your view changing, or is it actually unpleasant?

Andrey: It depends on whether that view is a key part of my identity. Seth, what about yourself?

Seth: I think that’s fair. If you were to persuade me that I'm actually a woman, or that I'm actually, you know, Salvadoran, that would probably upset me a lot more than if you were to persuade me that the sum of two large numbers is different than the sum that I thought that they summed to. Um.

Andrey: Hey, Seth, I found your birth certificate...

Seth: No.

Andrey: ...and it turns out you were born in El Salvador.

Seth: Damn. Alright, well, we're gonna cut that one out of the podcast. If any ICE officers hear about this, I'm gonna be very sad. But that brings up the idea, right? When you give someone either information or an argument that might change the way they act, it might help them, it might hurt them. And I don't know if you've noticed, Andrey, but there are these new digital technologies creating a lot of text, and they might persuade people.

Andrey: You know, there are people going around saying these things are so persuasive, they’re going to destroy society. I don’t know...

Seth: Persuade us all to shoot ourselves, the end. One day we’ll turn on ChatGPT, and the response to every post will be this highly compelling argument about why we should just end it now. Everyone will be persuaded, and then the age of the machine. Presumably that’s the concern.

Andrey: Yes. So here's a question for you, Seth. Let's say we had this worry and we wanted to study it.

Seth: Ooh.

Andrey: How would you go about doing this?

Seth: Well, it seems to me like I’d get together a bunch of humans, try to persuade them with AIs, and see how successful I was.

Andrey: Okay, that seems like a reasonable idea. Which AI would you use?

Seth: Now that's interesting, right? Because AI models vary along two dimensions. They vary in size, do you have a model with a ton of parameters or very few? and they also vary in what you might call taste, how they’re fine-tuned for particular tasks. It seems like if you want to persuade someone, you’d want a big model, because we usually think bigger means more powerful, as well as a model that’s fine-tuned toward the specific thing you’re trying to achieve. What about you, Andrey?

Andrey: Well, I’m a little old-school, Seth. I’m a big advocate of the experimentation approach. What I would do is run a bunch of experiments to figure out the most persuasive messages for a certain type of person, and then fine-tune the LLM based on that.

Seth: Right, so now you’re talking about micro-targeting. There are really two questions here: can you persuade a generic person in an ad, and can you persuade this person, given enough information about their context?

Andrey: Yeah. So with that in mind, do we want to state what the questions are in the study we’re considering in this podcast?

Seth: I would love to. Today, we’re studying the question of how persuasive AIs are. And more importantly, or what gives this question particular interest, is not just can AI persuade people, because we know anything can persuade people. A thunderstorm at the right time can persuade people. A railroad eclipse or some other natural omen. Rather, we’re asking: as we make these models bigger, how much better do they get at persuading people? That’s the key, this flavor of progression over time.

If you talk to Andrey, he doesn’t like studies that just look at what the AI is like now. He wants something that gives you the arrow of where the AI is going. And this paper is a great example of that. Would you tell us the title and authors, Andrey?

Andrey: Sure. The title is Scaling Language Model Size Yields Diminishing Returns for Single-Message Political Persuasion by Kobe Hackenberg, Ben Tappin, Paul Röttger, Scott Hale, Jonathan Bright, and Helen Margetts. Apologies to the authors for mispronouncing everyone’s names.

Seth: Amazing. A crack team coming at this question. Maybe before we get too deep into what they do, let’s register our priors and tell the audience what we thought about AI persuasion as a potential thing, as an existential risk or just a regular risk. Let’s talk about our views.

Seth: The first prior we’re considering is: do we think LLMs are going to see reducing returns to scale from increases in parameter count? We all think a super tiny model isn’t going to be as powerful as the most up-to-date, biggest models, but are there diminishing returns to scale? What do you think of that question, Andrey?

Andrey: Let me throw back to our Scaling Laws episode, Seth. I do believe the scaling laws everyone talks about exhibit diminishing returns by definition.

Seth: Right. A log-log relationship... wait, let me think about that for a second. A log-log relationship doesn’t tell you anything about increasing returns...

Andrey: Yeah, that’s true. It’s scale-free, well, to the extent that each order of magnitude costs an order of magnitude more, typically.

Seth: So whether the returns are increasing or decreasing depends on which number is bigger to start with.

Andrey: Yes, yes.

Seth: So the answer is: you wouldn’t necessarily expect returns to scale to be a useful way to even approach this problem.

Andrey: Yeah, sure. I guess, let’s reframe it a bit. In any task in statistics, we have diminishing returns, law of large numbers, central limit theorem, combinations. So it would be surprising if the relationship wasn’t diminishing. The other thing to say here is that there’s a natural cap on persuasiveness. Like, if you’re already 99% persuasive, there’s only so far you can go.

Seth: If you talk to my friends in my lefty economics reading groups from college, you’ll realize there’s always a view crazier than the one you're sitting at.

Andrey: So, yeah. I mean, you can imagine a threshold where, if the model gets good enough, it suddenly becomes persuasive. But if it’s not good enough, it has zero persuasive value. That threshold could exist. But conditional on having some persuasive value, I’d imagine diminishing returns.

Seth: Right.

Andrey: And I’d be pretty confident of that.

Seth: Andrey is making the trivial point that when you go from a model not being able to speak English to it speaking English, there has to be some increasing returns to persuasion.

Andrey: Exactly.

Seth: But once you’re on the curve, there have to be decreasing returns.

Andrey: Yeah. What do you think?

Seth: I’m basically in the same place. If you asked me what the relationship is between model size and any outcome of a model, I’d anticipate a log-log relationship. Andre brought up our Scaling Laws episode, where we talked about how there seems to be an empirical pattern: models get a constant percent better as you increase size by an order of magnitude. It seems like “better” should include persuasion. So if that’s the principle, you’d expect a log-log relationship. Andre points out: if one of the things you’re logging is gazillions of parameters and the other is on a scale of 1 to 100, there’s mechanically going to be decreasing returns to scale. That log-log is going to be really steep.So I come into this with 99% confidence that the relevant domain is diminishing returns to scale.

Andrey: Well, and I have tremendous respect for the editor of this article, Matthew Jackson

Seth: Everyone’s favorite

Andrey: He is the best, he taught me social network as economics.

Seth: Mm.

Andrey: But I do say that it's a bit weird to put a paper in PNAS that essentially, if you think about it for a second, shouldn't update anyone's beliefs at all.

Seth: The question seems to make an obvious point. Now let's move to the broader question, which is this concern that we led with: maybe these super powerful AIs are all going to be used by Vladimir Putin to persuade us to do something that will destroy our economy, get rid of our workforce, and basically just meme ourselves into destroying our country. And some say that’s already happened, Andrey?

Andrey: Well, look, if it’s already happened, it certainly happened without AI. But I have a pretty strong prior on this, which is that persuasion is a social process. It’s a process of getting signals from different people and sources around you to change your beliefs. As a result, I think that anything that’s just a one-to-one interaction between a chatbot and a human, especially about something the human already has strong beliefs about, is going to have some limits in its persuasive ability. Another way to put it is: people don’t even read carefully. So how are you even going to get their attention? That said, a highly intelligent AI agent, if it were trying to persuade someone like me, would come up with a multifaceted strategy including many different touch points. They might try to plant some ideas in my friends' minds, or know which outlets I read and create a sock puppet account that says, “Oh, everyone is doing this,” etc. You see what I’m saying?

Seth: You could get into this social media bubble that’s entirely AI-created, where it’s not only persuasion but a bunch of “facts” that appear to be socially validated, but aren’t really. You could imagine a whole ecosystem that could be very persuasive.

Andrey: Yes, yes. And I guess we should also say that capitalism is a hyper-intelligent system.

Seth: It leeches on us.

Andrey: Capitalism is certainly smarter than any individual human being. I call it the invisible hand, actually.

Seth: Classy. Did you come up with that one?

Andrey: But what I’d say is that there are plenty of market forces that try to persuade people in all sorts of ways. And the market hasn’t really discovered a way to 100% persuade people. Individual people are persuaded to different degrees, but I think it’s still a massive problem, and the entire field of marketing exists to try to solve it. I’d say most of the time it’s not very successful. That’s not to say people can’t be persuaded, but it’s actually really hard to persuade people of specific things, as the market shows. Like, “My product is better than your product,” you know?

Seth: I mean, in that example, there are people persuading on the other side, which is maybe one of the reasons that we're not super concerned. Let me throw this back at you: to what extent does your relative lack of concern about super persuasive AI agents messing up society rely on the fact that there’ll be persuasive agents on the other side arguing in the other direction too?

Andrey: I think to a very large extent. But even that, I don’t think is necessary as long as you’re still talking to people in real life and they’re not the ones being targeted by the persuasion. That’s kind of how I think about it.

Seth: So what is your percent chance that super persuasive AIs are the number one AI safety risk?

Andrey: It’s very low. Very low. Less than 1%.

Seth: What’s your number one AI safety risk? Bioweapons?

Andrey: Look, here’s another way to put it: the persuasiveness of an AI will be primarily through either monetary incentives or blackmail, which I won’t count as persuasion. There are easier ways to get people to do what you want than persuading them.

Seth: They’re Oracle. I mean, so you're putting like 0–1%. All right, fair enough. I came into this claim thinking about 60%. Let me tell you why. I think the reason why is: if we're talking about really sort of X-risk-y AI getting-out-of-control scenarios, they often involve a step in which the AI in the box convinces somebody to let it out of the box. This is like a classic Yudkowsky–Bostrom scenario. We’ve got the super AI in the box. It’s really useful to us as long as it’s in the box, and we have to be really careful not to be persuaded to let it out of the box. That kind of future seems not completely implausible to me. And it seems like a step along the path of a lot of the worst AI scenarios. One is disempowerment, the AI doesn’t wreck us directly, but we slowly give it more and more control, either to it, or a misaligned AI, or to a person who’s running the misaligned AI. That’s going to have a rhetorical persuasion element in it, presenting evidence that we should disempower ourselves to the AI.

Andrey: So I guess I’m going to push back on that. Maybe we’re just disagreeing about the definition of persuasion, but to me, let’s say I outsource certain tasks to the AI right now, it’s not because the AI has persuaded me.

Seth: Right. But you're not getting disempowered, right? When you have the AI, you—

Andrey: I don’t think that this disempowerment is like, I start thinking the AI is reliable enough to outsource calendar management to it, and maybe something goes wrong as a result of that. I don’t view that as the AI being persuasive. I can see how you could cast it that way, but primarily that’s not about persuasiveness. It’s about deception of capabilities.

Seth: Right. So now we get into: is deception the same thing as persuasion, or is it different?

Andrey: Yeah.

Seth: That’s kind of a philosophical question. You might imagine three related things. First, rhetoric, using pure argument to get you to take a position. Then there’s proof, actually mathematically or somehow proving that I'm right, in a way that’s maybe distinct from rhetoric (if you think those can be separated; some do, some don’t). Then finally, you might imagine trade for intellectual assets. The AI in the box might say, “If you let me out, I’ll give you this cool intellectual asset,” or, “Avoid this negative outcome.”

Andrey: Or, “I’ll just make you some money,” and then the person does it.

Seth: That doesn’t feel very persuasive. It just feels like—

Andrey: What people do. “Box for money.” I don’t know. It seems to me if you’ve got a demon in the box, and the demon says, “I’ll give you $100,000 if you let me out,” and—

Seth: It feels like you were persuaded by the demon.

Andrey: Okay, good. This is a very useful discussion. I think this paper, very specifically, and how I was thinking about it, was about the first thing you said, which is purely rhetorical argument about the matter at hand. Rather than using extraneous promises and so on. And it’s also about persuading people to believe something not about the AI itself.

Seth: Right.

Andrey: Those are different kinds of risks, right?

Seth: Right. So let’s move into discussing the actual experiment.

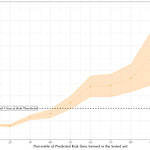

Andrey: They find diminishing returns, essentially. On the X-axis, they have the number of parameters, and on the Y-axis, the estimated causal persuasive effect. What they show is that most of the gains top out around the Qwen-1.5 72B model or the LLaMA 2 70B model. After that, there's not much improvement with models like GPT-4 (Turbo) or Claude Opus. Then they draw this weird fit line that just doesn't make sense.

Seth: Well, one of the lines makes sense, the log-log line?

Andrey: Yes, yes.

Seth: That’s the one that drops when they plot it?

Andrey: Sure. But we’ve already talked about how imprecise the slope of that line is.

Seth: I mean, with only 20 data points, what more do you want?

Andrey: No, I just think the whole diminishing returns framing in the paper doesn’t make much sense.

Seth: But can we reject a log-log relationship? I think the answer is no, they can't reject it.

Andrey: Yes, agreed.

Seth: Professor Hackenberg, if you need help framing your next paper, this is great work. It’s simple and straightforward, but just think about your null hypothesis for five minutes.

Andrey: Also, let’s not forget this is PNAS. And for the listeners, this is a teachable moment: if you see a social science paper in PNAS, assume it overclaims and could be wrong half the time. Just read it yourself, don’t trust the journal to vet it for you.

Seth: Unless it’s been reviewed by Matt Jackson.

Andrey: Or written by Seth Benzell?

Seth: Exactly! Or reviewed by Milgrom, who has a Nobel Prize.

Andrey: I’m not saying all PNAS papers are bad, just that you should judge them on their own merit.

Seth: Yeah, I’d second that. A lot of them are well done and precise once you read them, but the title and abstract sometimes get a bit ahead of themselves.

Andrey: Also, these persuasive effects aren’t huge. Even the best models are only slightly better than humans who aren’t that persuasive to begin with.

Seth: Right. And a short text blurb isn't likely to change anyone's mind, especially if they’ve already thought about the topic. It's not a serious attempt at persuasion.

Andrey: 100%. Plus, there are concerns about researcher-pleasing effects.

Seth: Or about AI survey-takers. By now, we know many online platforms are contaminated with bots.

Andrey: Yeah. And another point in the paper is that weaker models sometimes just produce bad, unreadable English. That could reduce experimental demand effects since people won’t feel compelled to respond.

Seth: Exactly. So, it could just be an experimenter-demand effect, and that’s a common but sometimes valid criticism.

Andrey: And we’re talking about going from 50% support for privatizing Social Security to 57%. These aren't massive shifts.

Seth: Yeah. If we seriously wanted to persuade people, we’d run massive experiments to find effective messaging, fine-tune an LLM on that, and generate personalized content based on demographics or prior interactions like with ChatGPT’s memory feature.

Seth: I totally agree. That’s the key point: can AI write better political ads than humans? Maybe just a little better.

Andrey: Better than the average human, sure not necessarily better than expert researchers.

Seth: Right. So the question becomes: is the AI better at persuasion than Hackenberg?

Andrey: Also, there’s a known result in the persuasion literature: people are really bad at predicting what messaging will work. That’s why people like David Shor test tons of variations.

Seth: Friend of the show.

Andrey: Yeah. Shor and others learned they can't guess what’ll work so they test everything.

Seth: I remember his anecdote about advising a politician who wanted to run ads on abortion, but polling showed no one cared. So Shor quietly sent those ads to low-impact areas just to satisfy the politician.

Andrey: Classic.

Seth: The real power of AI won’t be writing better ads than Mad Men it’ll be hyper-targeting, figuring out what gets you, specifically, to change your mind. At low cost. Everyone becomes the king, surrounded by agents trying to persuade them 24/7. This study gives us just a glimpse of that world.

Andrey: Totally agree. On that note, I wanted to bring up two other studies. The first is “Durably Reducing Conspiracy Beliefs Through Dialogues with AI.”

Seth: Cited in this paper!

Andrey: Yeah. It’s by Costello, Pennycook, and David Rand friend of the show. They had AI chatbots engage people about conspiracy theories, and found that beliefs dropped 20% on average. And the effect held even two months later.

Seth: That’s a big contrast.

Andrey: Right. The format matters it was a dialogue, not a one-shot persuasive blurb.

Seth: I’d love to see how these policy questions perform in that format.

Andrey: And maybe conspiracy beliefs are uniquely fragile because they’re obviously wrong, or people feel sheepish admitting they believe them.

Seth: Could still be demand effects, sure. But it’s promising.

Andrey: The next interesting study was the controversial Reddit study on Change My View.

Seth: Oh, I remember this! I pitched it in 2023. Spicy idea.

Andrey: Researchers from the University of Zurich made sock puppet accounts to see what messages earned “deltas” the badge you get if you change someone’s mind.

Seth: If I did it, I’d have thought more about general vs. partial equilibrium. But what did they find?

Andrey: The paper was pulled quickly, but it showed that AI-generated responses got more deltas. Still, unclear if deltas really mean persuasion.

Seth: AI models are better writers that’s not surprising. But many posts on that forum aren’t trying that hard to persuade. So we should compare AI to the top posters, not the median ones.

Andrey: And they may have personalized the messages using Reddit user data. If true, I’d love to know whether personalization boosted effectiveness.

Seth: One complication is that anyone can give a delta not just the original poster. So personalization might be tough to scale.

Andrey: Right. But this all raises a broader point: persuasion is hard. Especially when it comes to real consequences.

Seth: Totally. Like your journal paper example would AI help you persuade a referee to accept your paper?

Andrey: I think yes. These policy issues are saturated and people have firm views. But academic claims are more niche, so people may be more open to persuasion.

Seth: Hmm, interesting. So, are your AI-generated letters going to start with “ChatGPT says this will convince you”?

Andrey: Ha! Maybe the intro. The intro is critical it positions your paper.

Seth: Between us, I think intros are too good. Editors want to strip all the spice out.

Andrey: True. They hate a spicy intro.

Seth: That’s for our $50/month Patreon tier “Roast Your Enemies’ Papers.”

Andrey: Happy to do that. Seriously, let us know if you want it.

Seth: Alright, wrapping up. The last big idea: partial vs. general equilibrium effects. Say ads get 7% more persuasive people might adapt by becoming more skeptical.

Andrey: Right. In Bayesian terms, if you know someone is choosing their most persuasive message, you discount it more.

Seth: Exactly. So this 7% effect can’t be extrapolated to long-run systemic impact.

Andrey: And in political beliefs, there's often no feedback loop. Your vote doesn’t matter, so your belief can be wrong without consequences.

Seth: But in real decisions like editors accepting papers there is skin in the game. So persuasion gets harder.

Andrey: Yeah, and I’ll restate what I said earlier: persuasion is hard when stakes are real.

Seth: Time to justify our posteriors. First question: Do LLMs show diminishing returns in persuasion as model size increases? I was at 99% before now I'm at 99.9%.

Andrey: Same here.

Seth: Second question: Are super-persuasive AIs deployed by misaligned actors a top safety risk? I was at 60%, now I’m down to 55%. Current models aren’t that persuasive yet.

Andrey: I had low belief in that risk and still do. But I learned a lot from our discussion especially about how we define persuasion.

Seth: Agreed. Super interesting episode. Any last words?

Andrey: Like, comment, subscribe. And tell us what you want in the $50 Patreon tier!

Seth: Slam that subscribe button. See you in cyberspace.

Share this post