Could AI Save Us From Making Hard Choices About the Budget?

It may make current obligations in the developed world easier to meet, but that doesn't necessarily make debt wise

The “Big Beautiful Bill”, just signed by the President, is projected to increase US indebtedness by $3 Trillion Dollars. US Debt to GDP, already projected to hit about 110% of GDP in 2030, will reach 115% instead.1

Is this spendthrift fiscal policy a problem? Economic analysis suggests at least two reasons.

The subtle reason is that government spending2 can “crowd out” private investment. When savers invest in government bonds (or have their savings taxed away), those funds don't flow into the stock market or startups. If private investment is needed to take advantage of a new technology, government borrowing and taxing might slow that down.

The dramatic reason is the inevitable crash when the party stops. Eventually people will stop lending to the government, and then it will need to either inflate the debt away, default on the debt explicitly, and/or accept harsh austerity budgets. A recent analysis by the Penn-Wharton Budget Model lays out what this negative spiral might look like for the US.

The ubiquity of these negative outcomes was memorably recorded by master economists and Microsoft Excel novices Reinhart and Rogoff in the ironically titled This Time is Different.

With this most recent expansion of the debt, commentators have begun to point to a new reason that this time might really be different. One representative Twitter post reads:

This take has even been echoed by Silicon Valley’s favorite economist,

A related point has been made by Peter Thiel in a recent interview

As Thiel points out, it seems like more people should be thinking about the details of how AI-driven productivity growth will play out for budgets and geopolitical power.

Luckily, my colleagues and I at the Stanford Digital Economy Lab are working on just such an analysis! Keep reading to see:

What does our detailed international macroeconomic simulation have to say about the sustainability of government debt during an AI-driven economic boom?

What does our simulation model leave out, and what other considerations should we bring in, as we make decisions about the US deficit? Deficits in other countries?3

Simulating the Global Effect of Transformative AI is a recent whitepaper by myself and Victor Ye investigating the international distributional, growth, and fiscal outcomes of a set of specific AI scenarios. To do so, it integrates a model of AI-driven productivity and automation with the state-of-the-art CGE-OLG (computable general equilibrium, overlapping generations).4 This work is based on Victor Ye’s dissertation chapter Simulating Endogenous Global Automation.

The scenarios we examine treat AI not as leading to a finite time economic singularity, but still a large scale economic boom on the scale of a new Industrial Revolution. In this scenario, over the course of the next 35 years, the world slowly gets access to technologies that can automate a large share of human labor — reducing labor’s importance to output by about half by 2060 (see footnote for details).5 That said, many of the arguments below hold directionally for more or less extreme AI-booms.

So let’s dive in, and answer the question, is unlimited debt ok in the age of AI? — sure, it’s never worked for anyone before, but maybe…

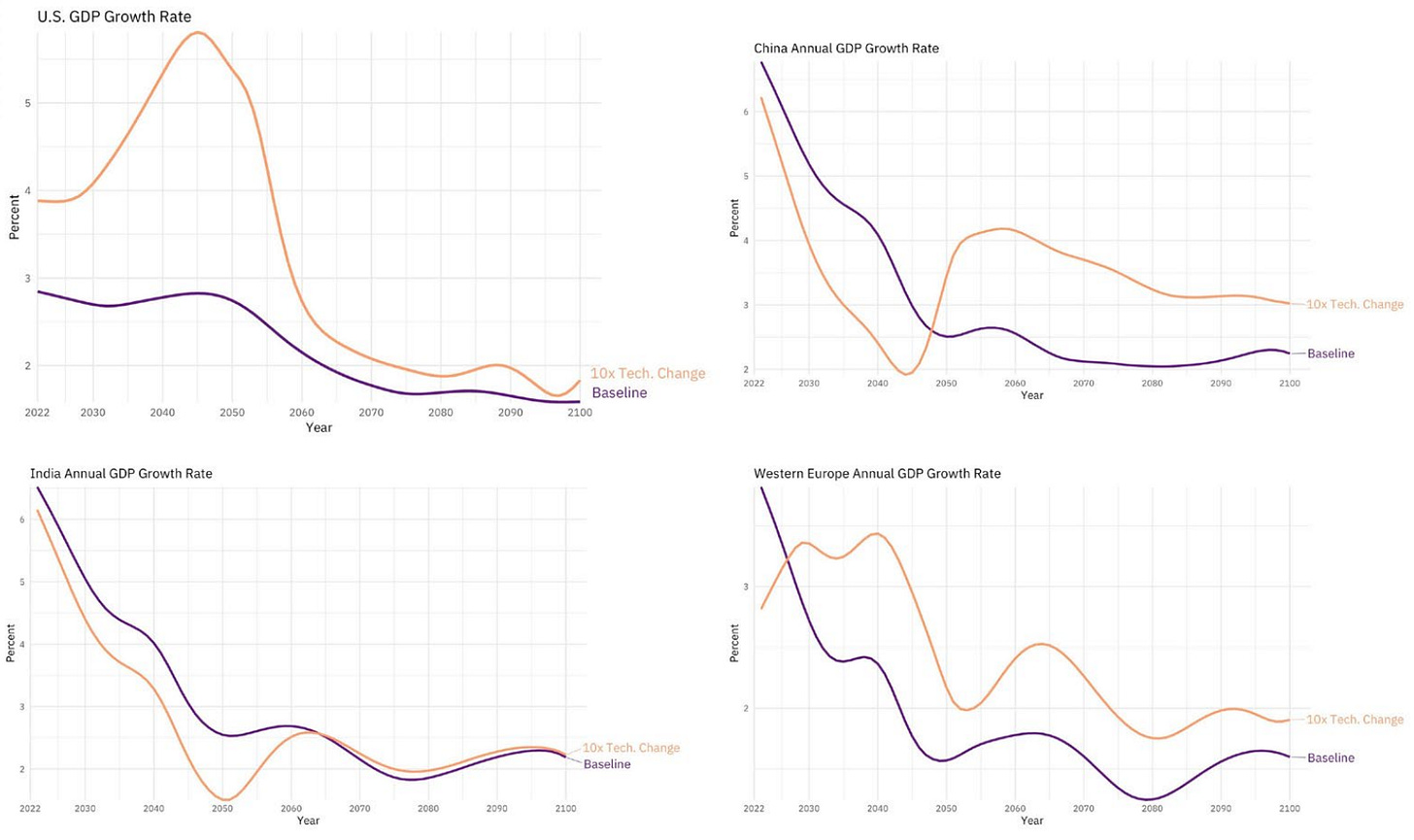

Let’s start with the good news. One way AI could help make the debt more sustainable would be by helping the US “grow out of” its many looming fiscal crises. And indeed, the AI scenario we consider would be a massive GDP growth boost to the US: increasing GDP growth rates by 1-3 percentage points throughout the wave of automation.

This is obviously very good news. More output (even if some of it is owned by foreigners investing in the US — more on this later) makes it easier to solve all social problems — the deficit included.

The clearest problem that this solves are the pension obligations the US has through its pay-as-you-go Social Security system. Because these pensions are tied to wages (mostly pre-AI boom, but some post by 2060) they’ll be easier to pay back in terms of share of GDP that needs to be taxed.

US spending on Social Security is a bit under 4% today, and our baseline projection has total US Government pension obligations rising to 5.7% of GDP in 2060. However, given an AI productivity boom, pension benefits are projected to only cost 2.9% of GDP in 2060.

For other government programs, the assumption that costs will not grow as national income expands is more dubious — and I’ll come back to that point. But if we can stop expanding spending while GDP grows, this massively helps balance the budget: The sum of health, pension, disability, education, and other (including military) expenditures falls from 34% of GDP in 2060 in the baseline to 17% assuming an AI productivity boom.6

Wow, 17 percentage points of GDP to play with in the budget! Seems pretty sustainable right?

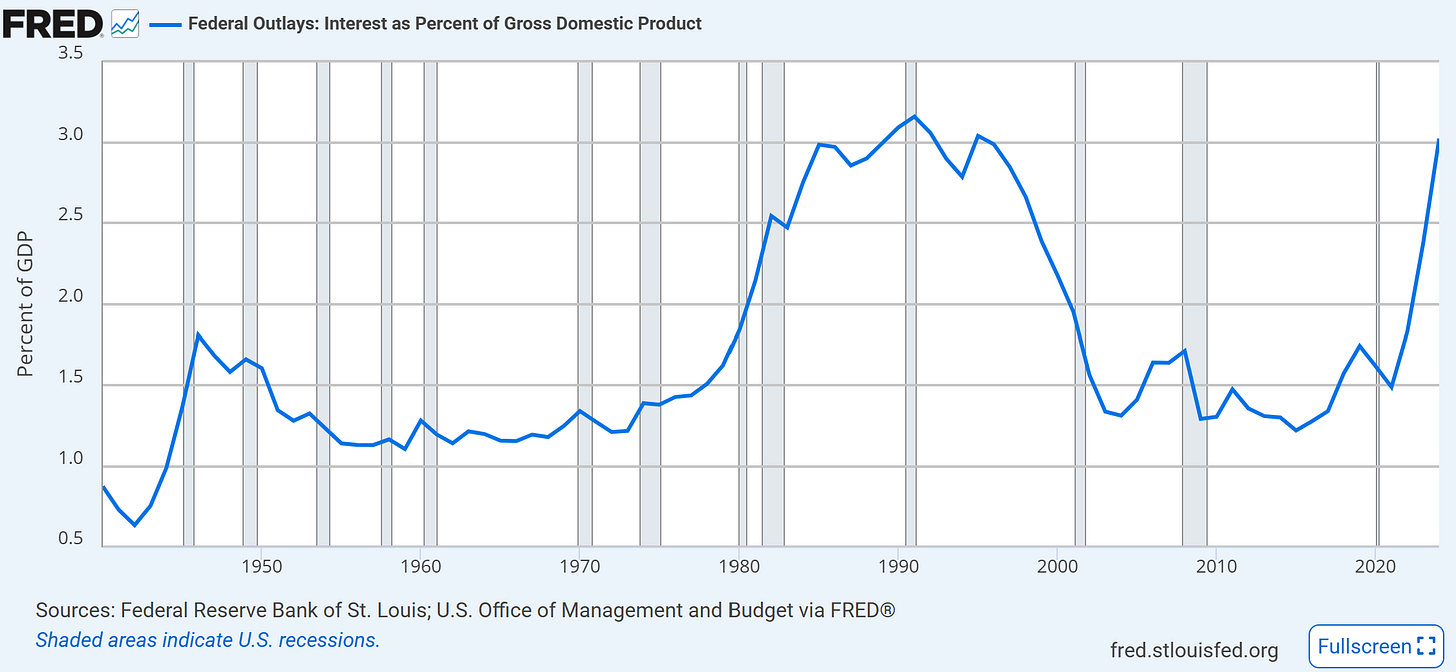

Now for the bad news. There’s one big line item in the budget we haven’t mentioned yet — interest on the national debt. In 2017 the government’s borrowing costs were at record lows (1.2% of GDP), but have exploded upwards since.7 In 2024, the US spent over 3% of GDP paying interest on the national debt.

This line item will not get smaller with the AI productivity boom. Instead, the opposite. This is because an AI boom will make it costlier for the government to borrow money.

The reason is that all the exciting opportunities in AI will bid up interest rates. At a point in time, there is only so much of output being set aside for investment. A dramatic advance in AI tech is, primarily, an invitation to make a new, very productive investment. It means taking a few days off to reskill, or using the company credit card to subscribe to the AI service, or looking for angel investors in your new AI application idea.

How much do interest rates go up because of the AI boom? In our scenario they go up by about 4 percentage points, indefinitely — more than double their projected value under the baseline scenario. 8

Although AI productivity boom would increase GDP, it would also massively increase interest rates and the cost of capital. That’s very bad for debtors, and agents with high inter-temporal discount rates.9 And, from a fiscal perspective, the US government is the biggest, most impatient agent out there.10

What do we find? In such a scenario, the global real rate of return increases by 4 or more percentage points by 2060 (vs no AI boom), and stays elevated indefinitely. Meanwhile, the US growth rate is 1-3 percentage points elevated until 2060 with extra growth small after that period.

This effect would make the debt harder to sustain. It may push r>g (i.e. interest on the national debt is greater than the growth rate). Public economists are wary of debt in these circumstances because debt to GDP grows even if the primary budget (the budget before taking R into account) is balanced.

But, at least in our scenario, the fiscal negatives from the higher interest rate are much smaller than the benefits from growth. Even if the US cost of borrowing were to triple, this would only raise the cost of paying the national interest to 9% of GDP. This is a massive number — but still much smaller than the fiscal space we’re supposedly creating by growing out of our welfare obligations. In our simulation, they rise to only 4.5% of GDP, even more manageably.

On net then, given this scenario and assumptions, the US is projected to spend much less as a share of GDP in 2060 because of the AI boom, and this allows for lower average tax rates.

Now for the ugly part. While things go pretty well for the US budget in this scenario, other countries don’t fare nearly as well.

The reason is that while the increase in interest rates is global, only the most advanced countries see major growth benefits from the AI boom. As I previously pointed out, an AI boom is an opportunity to make productive investments. If we think of this boom as, in part, coming from automating jobs then it immediately becomes apparent that some countries will benefit more from AI than others.

The countries that benefit the most from AI will be the ones with (currently) high wages and TFP, and low costs of capital — the US is the lead example here, with high wages, a well developed financial system, and low corporate taxes.

On the other hand, regions in the developing world with low initial wages and TFP, and difficulties in borrowing and investing, benefit less from the opportunity to automate labor. This means that people with money to save in the developing world will increasingly be investing their money into the US. This will get residents of the developing world a higher rate of return, but it is the US residents who will benefit from the investments.

One example my coauthor Victor likes to use is that American firms make T-shirts in a highly automated fashion. He has had T-shirts printed in Brooklyn by companies that use almost zero labor. But nobody in India would voluntarily purchase such a machine because local borrowing is expensive and the servicing costs of said capital investment is more expensive than the Indian workers it replaces.

While the US benefits the most from the AI-boom, Western Europe and Japan also do well. India actually sees depressed growth due to capital flight. China is a mixed case, in the short term facing capital flight, and lower growth than otherwise, but eventually adopting and benefiting from the frontier AI technology.11

So the ugly truth is that even if the AI-boom is good for the US’s budget balance, the story is more mixed for the rest of the developed world, and even negative for the developing worlds’ balance.

So where does that leave us? Does an imminent AI boom make government debt a good idea? Or at least a less bad idea? The answer from our simulations, in terms of fiscal sustainability, is yes for the US, but no for many other regions. However, there are at least three factors to consider before we accept that simulation result:

The rise of AI-driven productivity is likely to be associated with large new demands for government expenditure. Most obviously, this this may include welfare payments for the newly unemployed, the costs of a new cold war with China or AGI race, and large energy infrastructure demands. There may be Baumol’s cost-diseases in whatever services the government wants to provide. More speculatively, expensive life extension techniques might be invented and demanded at subsidized prices by the public. This would be a large direct cost, and also keep around more pension check collecting retired Boomers.

Could these increased calls for government spending be large enough to keep up with GDP growth? It’s impossible to predict for sure. But, historically, Congress has had no problem rising to the challenge.

The wealth created by AI companies may be difficult to tax, because intellectual property may be relocated to low corporate tax countries.

What makes OpenAI such a special and valuable company? It’s not the chips it owns — those are commodities. Their value is in their intellectual property and, to a certain extent, in the contracts it has with highly productive employees. While workers may not be able to easily relocate (and therefore, we should be able to hit them with income and consumption taxes) the intellectual property inside OpenAI, the thing that profits that are ascribed to and would be taxed, might be able to flee to a tax haven.12

In a world that is fully hurtling towards singularity — with very few humans providing useful work — this effect would be even stronger. We might see a colony of the ultra elite and their massive robot factories setting up in Antarctica (for the low taxes and to chill the graphics cards racks), a charter city in the Sahara (for the solar power and no need to worry about pollution), or somewhere stranger like beneath the ocean. In these scenarios, the US would only be able to benefit tax-revenue wise from taxing trade with these ultra elites — perhaps us selling them the few resources that they had yet to automate.

A technologically advanced tax-haven charter city for the worlds’ elite in a remote location? What could go wrong? Art found here. Now, perhaps this could be solved by an international agreement to set a minimum global corporate tax. This would minimize the risk of OpenAI or Anthropic etc. locating their IP in a tax haven. As of 2024, there was good progress towards just such an…

haha well…

Additionally, many of the benefits from AI may come in the form of intangible improvements in digital consumption goods. DEL research on intangible digital product quality improvement has shown these gains to be a big part of recent welfare improvements. This might be real growth, that really raises welfare, but will be hard to tax or even measure. How do you tax all music and movies and video games getting 10% better, if costs or prices never change?Anticipated AI productivity growth will increase interest rates, and therefore the cost of financing government debt, before large productivity and government revenue benefits, because of investors forming rational expectations and attempting to hedge risk.

, research previously highlighted at Marginal Revolution.

This is an important point. The US debt has an average maturity of just under 6 years. Therefore, if the AI investment boom — or an AI optimism led dissaving boom — were to happen significantly before the AI productivity boom, then this would create (at least) short-term challenges for financing spending.

For a full discussion of how and why a spike in interest rates might significantly antecede a spike in growth rates, I highly recommend the excellent Transformative AI, existential risk, and real interest rates, by DEL’s own

Those caveats aside, it seems an AI-boom would make government debt more sustainable, at least for the US. But would it make it more wise?

I would make the case that the rise of very productive AI technologies actually increases the importance of government indebtedness as a social problem worthy of our attention.13

In a phrase, the reason why is “crowding out of private investment.” AI tech is, primarily, an invitation to make a new, very productive investments. If there isn’t lots of investment/saving to go around, you can’t take advantage of all these opportunities. And government taxes and debt are exactly the sort of thing that depresses investment. A short-termist government taxing the golden AI geese to give out short term goodies (or crowding out investment in them in the stock market by issuing bonds) is a problem, exactly if and when AI makes investment hyper-productive. Another way to say it is: “Even if AI technology is economically incredible, the social saving rate still matters!”14

To make the same point again — when the marginal cost of capital is high, that means there are productive uses for it that are being unexploited! Therefore, it’s even more important to save when interest rates are high.

This point doesn’t depend on my non-singulatarian stance. Even in a singularity, it would be the case that the social saving rate is very important. To make the exaggerated version of the point — even if we had the most fantastic AI technology available, if no one is willing to invest in making the next years’ NVIDIA chip factory, then we won’t get any output benefit.

Now, here’s the bit where I get a teeny tiny bit grouchy about the argument that AI means debt doesn’t matter.

I’m old enough (34) to remember when serious people used to make the exact opposite argument for deficits. Former IMF Chief Economist — the high priest of government debt if there ever was such a job — Olivier Blanchard argued that maybe, possibly, it was OK to go into massive debt when interest rates were low. To quote a talk abstract, "Put bluntly, public debt may have no fiscal cost.”

To paraphrase Olivier’s argument: In 2019 the safe interest rate was very low. This tells us that the rate of return on investment must be low too. In fact, there was so much saving looking for a safe home, it was leading to wasteful over-investment. The current generation (Boomers) could literally have a free lunch by borrowing or taxing "excess savings” to fund government spending today.

The logic had a certain perverse truth to it. If the future was so shitty, with so few investment opportunities, that giving our kids more resources or capital wouldn’t even be able to help them…. what’s wrong with the Boomers taking a bigger slice of the pie for themselves? Well, ok boomer. I guess it would be petulant for future generations to object to this immaculate logic.

OK, grouchiness over :)

Conclusion

The point of this essay is not to argue that an AI-driven economic boom would be a bad thing, because of the pressure it will put on government budgets. An AI driven boom would be an amazing thing, leading to huge additional wealth and welfare over time.

However, it will also raise the cost of capital and create new demands on government budgets. To meet these costs, government will either need to raise taxes, lower spending, or finance them with more debt. This creates two main concerns:

The first is simply the government’s ability to finance itself. The US already is faced with a straining budget. The Social Security Trust Fund is set to run out of money in 2033 and there is fiscal gap (a refined measure of the government deficit calculated as the difference between the present discounted value of projected spending less revenues by

) of 8% of GDP. Now, luckily, it might be that if we can keep spending on it’s current path, figure out a way to tax AI wealth, and the interest rate doesn’t go up early enough, then AI might be enough to wipe out that gap. But, as discussed, the idea that government won’t discover some new emergency to spend that fiscal space on is somewhat dubious.While some non-US governments are in stronger fiscal situations, with smaller debt/fiscal gap loads, they also will benefit much less from an AI-driven boom, making this an international challenge. The US may be able to get a slice of OpenAI wealth to fund itself, but Mexico and other middle and lower income countries will feel the squeeze of lower wages, higher interest rates, without an AI national champion’s revenue to compensate.

The second is the point that as interest rates go up, the social cost of government debt increases as well. There was a previously mainstream view that because real interest rate on government borrowing in the late 2010s were so low, it was ok for governments to go into debt. That’s because the social cost of government debt is proportional to the usefulness of the private investment it crowds out.

But — by that previously popular argument — when anticipated productivity is high, that’s exactly when we should be juicing the social saving rate.15

Instead of contemplating a larger debt, we should instead be talking about a national sovereign wealth fund, that could “own the robots on behalf of the people”. This would both boost output and welfare, and put the welfare system on an indefinitely sustainable path.

Thanks to

, , and for reviewing drafts of this post. Thanks to Victor Ye for helping with numbers and figures from our simulation.A fiscal gap analysis, a generalized measure of US indebtedness that takes into account all planned expenditures and revenues, finds that the US’s overcommitment amounts to 8% of the present discounted value of GDP — that is, 8% of output indefinitely. See

https://gsas.harvard.edu/news/colloquy-podcast-debt-ceiling-and-beyond-laurence-kotlikoffOr a speculative bubble

If this post is successful, in future essays I can discuss what the model has to say about the impact of an AI-driven economic boom for geopolitics/the international balance of power, and for the desirability of a “baby bond” such as the “Trump Accounts” in the BBB.

Called this because you model the entire world on the computer, as being made of people who are born, save, work and die over the course of overlapping lifespans. This is the same family of models used by the JCT and CBO in their projections.

The details of the model can be found in the working paper Simulating Endogenous Global Automation, but here’s an overview.

The world is divided into 17 regions. Within each region there are simulated agents in 3 different skill groups who live up to 100 years. So there are “300 representative agents” — each keeping track of demographic groups of different sizes — in the US or any other region at a point in time. These agents go through their lifecycles, giving birth to fractions of children each year which they care for, with some percent of them dying and inheriting from each other. They make decisions about how much to work, save, and consume in each year, taking the government’s tax policies and current and future prices as given.

Each region has a separate government which tax through wage, income, consumption, capital and corporate income taxation, and spend money on education, healthcare, direct transfers (e.g. welfare and disability), pensions (e.g. social security), and other (e.g. national security) programs. The U.S. is one of these regions. Each region’s government consolidates state, local and federal tax and spending policies, so if some of our government projected spending numbers seem a bit high, it’s because we’re including state and local taxation. In the scenarios considered, governments adjust their consumption and income tax rates (keeping their scaled progressivity fixed) in order to keep debt/GDP on an assigned path. Spending programs and corporate income and other tax rates they do not change.

There is also one representative firm in each region that hires workers and rents capital to make output. There is frictionless trade between regions.

A “Second Machine Age” (h/t

) if you will.The particular technology scenario I’ll focus on here is labeled “10x automation” in the paper. In this scenario, companies globally gain access to increasingly more productive technologies, which are also more capital intensive every year — i.e. more automated. But not every region’s company’s will use the most advanced technology — AI is most useful for countries with high wages and low costs of capital. Companies select which technology is best for them based on this, so not all countries will use the most advanced technology.

The size of the automation wave is 10x the speed at which capital’s share of income has increased in the past few decades. It proceeds smoothly each year. The boost to technological change ends in 2060, by which time capital’s share of income grows of 60 percent of GDP for regions at the the technological frontier — roughly speaking, you might say that the role of robots and capital are twice as large, and the role of labor half as large. The size of the productivity gain associated with automation is calibrated to historical estimates. For more details, see the white paper and working paper.

In terms of welfare, American workers see their share of output go down, but output overall goes up by a lot, their investment returns skyrocket, and tax rates fall because of the above effect, leaving them better off on net. This assumes that the AI isn’t further skill-polarizing, i.e. more high skill jobs are retained than low skill. For alternative scenarios where AI also changes the wage distribution among jobs that remain, see the white paper.

I bring up 2017 because that is when this model was calibrated. We would love to update the model with more recent data when we have the resources! It doesn’t matter for our other conclusions, but the increase in interest rates will therefore be about 2x worse for the budget in real life vs. the simulation for this reason.

Under the baseline scenario, interest rates would have decreased from today, driven by the wealth of a rising Asian middle class. This secular force driving down interest rates has been called the “global saving glut”. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-are-interest-rates-so-low-part-3-the-global-savings-glut/

That’s economics for “impatient idiots”

Who would have thought a House elected to two year terms might not have much foresight in drafting budgets?

Let us know if you want to hear about another region!

Contra TC, I think AI — which is easily sold across international lines, and might easily ‘locate itself’ through e.g. corporate inversions into a tax haven — calls for lower corporate tax rates. Automation generally makes the location of production more sensitive to capital taxation, making income + consumption taxation more attractive as well (the workers have to live in SF even if the bots don’t).

Also the chips will have to locate near cheap energy, which means to the extent the IP needs to be located where the chips are, this may prevent AI companies from just completely relocating to the Bahamas.

As I make this argument I want to clarify that I am not arguing that the US government shouldn’t ever borrow to make smart long-term investments. I don’t disagree with @AndrewCurran_ that extreme leverage can be optimal — If that leverage is allowing the US to make public investments (e.g. in energy infrastructure, or R+D) this could be wise. But the US government debt is NOT primarily about smart public infrastructure investments. The US government spends on welfare payments, interest on the national debt, and for national defense — in that order, with investments relatively small.

In Asimov’s “The Caves of Steel” the highly automated society is impoverished for just this reason — a short-term focused government suppresses savings, so there is a low ratio of automation capital to humans. My paper “Robots Are Us” explores a similar dynamic, where the lowered saving of the young, due to automation reducing their labor income, depresses growth rates. Reduced saving by young people does indeed slow global capital accumulation and growth somewhat in out 10x automation scenario.

Another way of saying the same thing is ”In an AK world, delta K is just as important as delta A”

Another caveat is that the US government is a big borrower, but not the only one in the world. If the US were to increase it’s social saving rate by reducing government crowding out, this would have a relatively small effect on the US itself, because of the global-ness of capital markets. This is mostly an argument about how the whole world needs to save more into an AI-boom, not the US in particular. However, to the extent that the world capital market is not completely open and free flowing, boosting US saving is likely to have a disproportionate impact on US investment.

The Trump Accounts — a version of Booker’s Baby Bonds — are an interesting but small idea in this direction. If anyone is interested in what our model has to say about a policy like this, check out the white paper.

Very interesting! I haven’t looked at the model in detail, but I was surprised to see the comparison with the Industrial Revolution and then at the same time growth rates going back to pre-AI levels after a while. In some discussions the Industrial Revolution is thought of as increasing growth rates by an order of magnitude, permanently. What’s the reason the model doesn’t predict that?

> While the US benefits the most from the AI-boom, Western Europe and Japan also do well. India actually sees depressed growth due to capital flight. China is a mixed case, in the short term facing capital flight, and lower growth than otherwise, but eventually adopting and benefiting from the frontier AI technology.

Why is this the case? Doesn’t China have a much higher savings rate with a higher inter temporal discount rate? I would expect China to primarily benefit from AI, or is it that China doesn’t have enough money, despite the savings rate and labor costs are still too low to justify automation, similar to your t shirt example?